top of page

Aurelia E. S. Browder

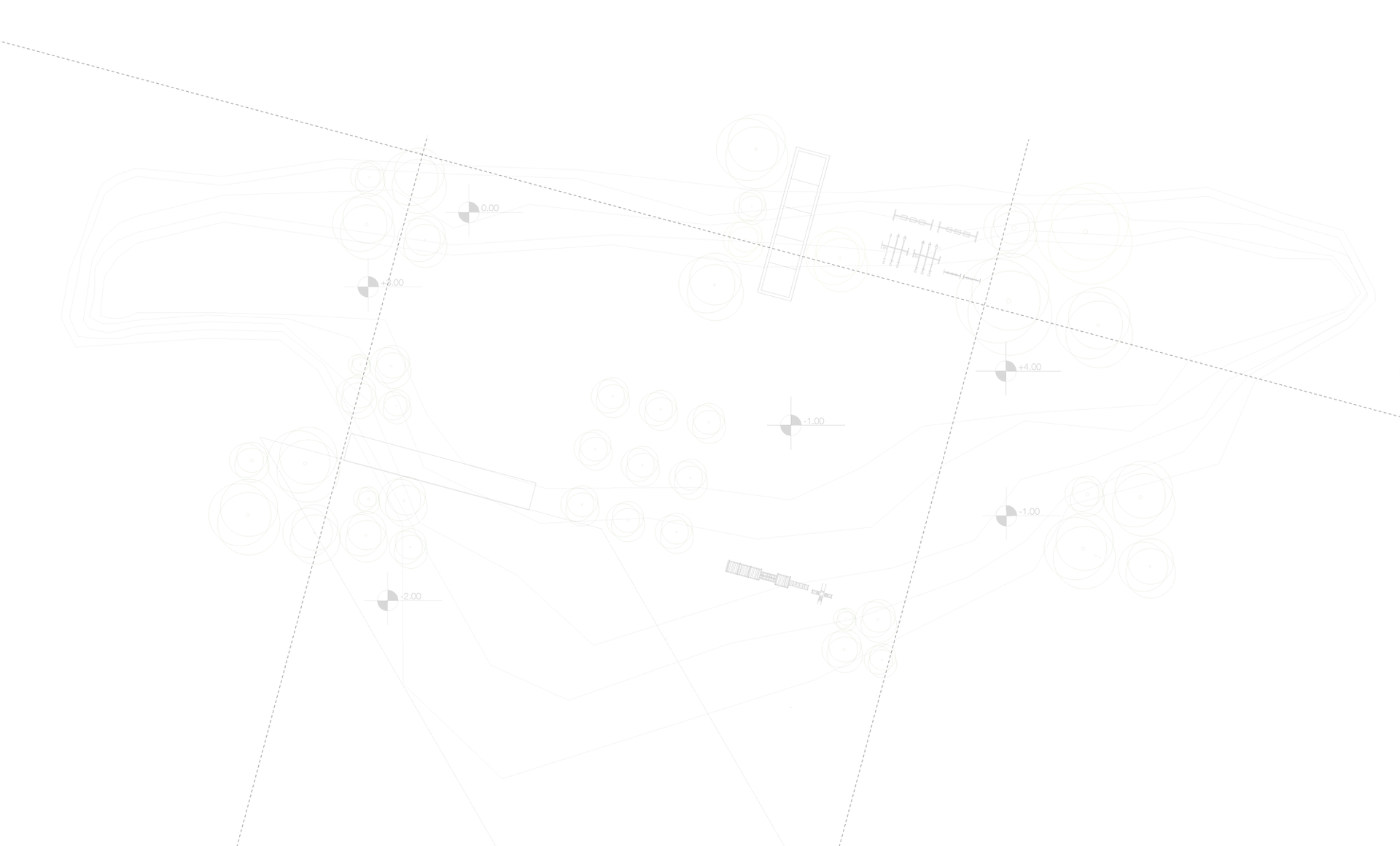

Historic House Museum in Montgomery, Alabama

Browder v Gayle - The landmark case that fueled the Civil Rights Movement

https://www.facebook.com/TheBrowderFoundation?ref=hl

Highlights of the landmark "Browder vs. Gayle" Case

Browder v. Gayle, 352 U.S. 903 (1956); Civil Action No. 1147.N

Aurelia E. S. Browder v. William A. Gayle challenged the Alabama state statutes and Montgomery, Alabama, city ordinances requiring segregation on Montgomery buses. Filed by Fred Gray and Charles D. Langford on behalf of four African American women who had been mistreated on city buses, the case made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld a district court ruling that the statute was unconstitutional. Gray and Langford filed the federal district court petition that became Browder v. Gayle on 1 February 1956, two days after segregationists bombed King’s house.

The original plaintiffs in the case were Aurelia E. S. Browder, Susie McDonald, Claudette Colvin, Mary Louise Smith, and Jeanatta Reese, but outside pressure convinced Reese to withdraw from the case in February. Gray made the decision not to include Rosa Parks in the case to avoid the perception that they were seeking to circumvent her prosecution on other charges. Gray ‘‘wanted the court to have only one issue to decide—the constitutionality of the laws requiring segregation on the buses’’ (Gray, 69). The list of defendants included Mayor William A. Gayle, the city’s chief of police, representatives from Montgomery’s Board of Commissioners, Montgomery City Lines, Inc., two bus drivers, and representatives of the Alabama Public Service Commission. Gray was aided in the case by Thurgood Marshall and other National Association for the Advancement of Colored People attorneys.

Because Browder v. Gayle challenged the constitutionality of a state statute, the case was brought before a three-judge U.S. District Court panel. On 5 June 1956, the panel ruled two-to-one that segregation on Alabama’s intrastate buses was unconstitutional, citing Brown v. Board of Education as precedent for the verdict. King applauded the victory but called for a continuation of the Montgomery bus boycott until the ruling was implemented.

On 13 November 1956, while King was in the courthouse being tried on the legality of the boycott’s carpools, a reporter notified him that the U.S. Supreme Court had just affirmed the District Court’s decision on Browder v. Gayle. King addressed a mass meeting at Holt Street Baptist Church the next evening, saying that the decision was ‘‘a reaffirmation of the principle that separate facilities are inherently unequal, and that the old Plessy Doctrine of separate but equal is no longer valid, either sociologically or legally’’ (Papers 3:425).

On 17 December 1956, the Supreme Court rejected city and state appeals to reconsider their decision, and three days later the order for integrated buses arrived in Montgomery. On 20 December 1956 King and the Montgomery Improvement Association voted to end the 382-day Montgomery bus boycott. In a statement that day, King said: ‘‘The year-old protest against city buses is officially called off, and the Negro citizens of Montgomery are urged to return to the busses tomorrow morning on a non-segregated basis’’ (Papers 3:486–487). The Montgomery buses were integrated the following day.

bottom of page